Understanding Execution Context

The rules of scope in JavaScript may seem confusing compared to other languages like JAVA or C++, but easier to understand if you consider Execution Context (EC), or the environment in which JavaScript code is evaluated and executed.

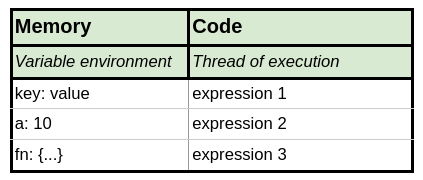

The EC can be visualized as a Node. Imagine the node as a block with a Memory and a Code section. It might be visualized like this:

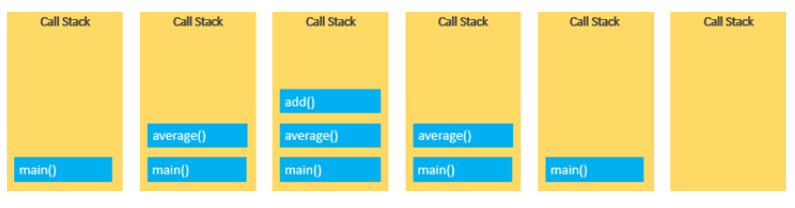

Javascript runtimes uses a call stack to manage ECs. A call stack behaves as a LIFO queue, meaning last-in-first-out.

JavaScript is a synchronous language, meaning that only one EC is running at a time. This may seem confusing since JavaScript has blocking methods like await, but we’ll come back to that topic in a later post.

When you start a JavaScript program, the engine creates a Global Execution Context, which is pushed onto the stack.

When a function is encountered, the engine creates a new Execution Context for the function and pushes it onto the stack and starts its execution.

When the current function completes, the JavaScript engine pops it off the call stack and resumes the execution where it left off.

The script stops once the call stack is empty.

https://www.javascripttutorial.net/javascript-call-stack/

Here is a visual example.

At any given time, the runtime environment (the browser or node if running on a server) is executing a single EC. Certain variables are visible to the EC’s function, and some external variables, which may exist in the local scope of other ECs are also visible.

Interestingly, an EC’s running function may have access to a variable defined in another function that was, at one time, pushed onto the call stack and has since been popped. More on this when we discuss Closure.

Consider this contrived example:

let x = 'Again, ';

function hello() {

let y = 'Hello ';

console.log(x, y, z)

function world() {

let z = 'World';

console.log(x, y, z)

}

}

hello()

Because z is not defined until the function world, it is not in scope for function hello. If you run this, you will receive a reference error: z is not defined. Let’s build our visual representations of the Execution Contexts for the example above.

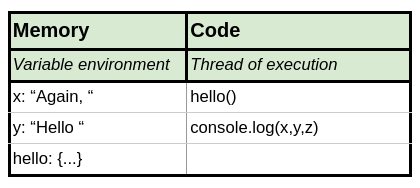

First the Global Execution context is built. It would look like this:

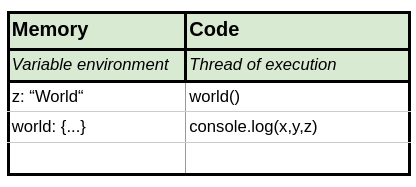

When the interpreter encounters the function world, it will create a second execution context.

Remember: an Execution Context has access to its memory, plus the memory of its parent, or the function that called it. So it has lexical scope.

In the first block, when the code console.log(x,y,z) is reached, there is no way to access a variable z, as its EC has no conception as to whether z exists.

However the second block can see z, because it is in its local EC, and x and y, because they are in the parent’s context. Think about this for a minute and make sure you understand why.

Let’s try again, removing our reference to z in hello, and adding a call to the child function.

let x = 'Again, ';

function hello() {

let y = 'Hello ';

console.log(x, y)

function world() {

let z = 'world';

console.log(x, y, z)

}

return world;

}

const childFun = hello()

childFun()

// output: Again, Hello

// output: Again, Hello world

Note:

- x is visible in global scope, hello scope and world scope

- y is visible in hello scope and world scope

- z is visible in world scope only

- x and y were not passed explicitly as arguments to their child functions

One way to think about EC is to consider it a function with access to its own local variables and a pointer to the variables defined within its parent’s function. Each EC has a pointer to its parents’ memory, so it’s much like a linked list.

To recap, conceptually:

- Execution Context a dual-purpose Node.

- This is a node that can be pushed onto a stack, executed, then popped off the stack.

- At the same time, each node’s memory is linked to its parent, forming a linked list.

Generally speaking, variables that are defined locally, or within a function, are always accessible within the function’s EC.

Variables that were defined in the calling function are also available.

In our example, while executing World’s Execution Context, the interpreter would look for the variables x and y in local memory, and when not found, will look to the parent context, and if not there, its parent context, all the way back up to the root node.

Note: This is a conceptual description of how a browser operates a call stack and actual implementation details will differ.

Stated differently, scopes are nested. When you see the phrase Lexical Scope remember that it means local scopes plus parent scopes.

Scopes

I hope that the proceeding explanation provided insight into how scope is handled fundamentally in Execution Contexts.

But JavaScript is a language with a long history and there are other special rules, some fundamental and some syntactical. I’ll summarize here.

Block Scope

- Any variable defined within a code block using the keywords let or const has block scope.

- Any variable defined with the keyword var within a block has global scope unless defined within a function.

Function Scope

- Any variable defined within a function using var, let or const will have function scope.

Module Scope

- Any variable, function or classes defined within a module are not visible outside the module unless the export keyword is used.

Nested Scope

- A scope within another scope is called inner scope.

- The wrapping scope is known as outer scope.

Global Scope

- Top level variables are global.

Lexical Scope

- Variables are accessible based upon their position with the nested function scopes.